Dear Friends,

Yesterday, a doctor stopped me as I went to clamber down from an exam table. She glanced at the braces that support my feet and ankles and then made me stop while she pulled out the step.

I would have been fine. The braces make it so that I’m much less likely to hurt myself doing precisely ordinary things like dropping myself down a short distance. They stabilize my gait so I don’t get hurt walking back and forth to the store or the train.

That doctor’s visit was my third specialist appointment in eight days. I spend a lot of time on activities that seem to respond to the question: “Do you want to be made well?”

But, the fact is, the answer isn’t exactly yes or no. It’s somewhere in between – which is why I feel confident in saying that this is a fraught question that Jesus asks the man struggling to get down into the waters near the Sheep Gate. According to the story, this man had been ill for 38 years, longer than Jesus would live, longer than I have lived so far. But I’ve spent enough time fussing about questions of healing and cure in this newsletter in the past. Reading this passage from John 5, I am struck particularly by the answer to this question.

Instead of responding regarding his desire (or lack thereof) to be healed, the man in this story replied, “Sir, I have no one to put me into the pool when the water is stirred up; and while I am making my way, someone else steps down ahead of me.”

Welcome to the social model of disability – one that points outward at the barriers in the world around us rather than inward toward our own perceived brokenness. This man has been doing his best to figure this out in his own way, to slowly negotiate the space as he was able to. His answer was not about his body, but about the space and the people about him. Jesus enters and circumvent the entirety of it – “Stand up, take your mat and walk.”

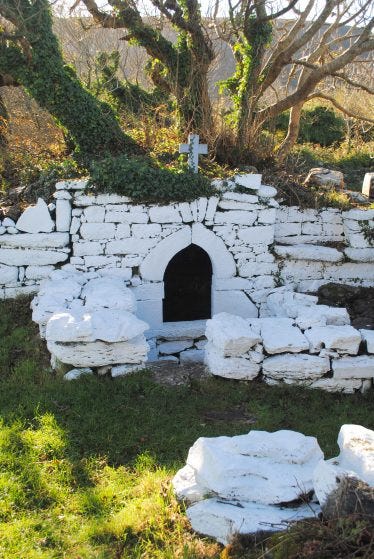

Holy Waters/Living Water

Evidence suggests that the pool described in this passage was a real one. And any time you’re at the gates of an ancient city, in those transition places, you’re likely to encounter the outcasts – including disabled people. And the same can also be said about many bodies of water; various pools, springs, and wells were known for their healing powers and people still visit some of these places today. Jesus’s question has a self-evident answer, then. The man in this story wouldn’t be at the pool if he didn’t want something to change.

But here’s the thing: we’re not miracle workers. We’re human. And we live and work and worship alongside other humans with bodies. When my doctor pulled out the step at the exam table, she fixed the path down. When we ensure our chancels are equipped with ramps or our basement church school classrooms with elevators, we make a way in our own environments.

Jesus was a miracle worker. He didn’t have to make a way down to the waters for the man in this story from John (which, thankfully, ends here, avoiding for us this week the distraction of what comes next - condemnation of Jesus’s healing someone on the Sabbath, as though that is a kind of “work” outlined in the law).

This passage invites us to imagine new possibilities. If our parishes or communities are like the pool near the Sheep Gate, a place people really do wish to be, a place that can we reshape the path to that place? When we cannot transform the entire world or an individual’s particular unchangeable realities, when we cannot say “pick up your mat and walk,” we can still make a way to the living water.

What Way Will You Make?

There isn’t precisely a Bible verse that says that God will make a way out of no way, but rather an array of verses that describe how God makes a way in the wilderness or a way of escape or a path in the waters. But we have a habit of feeling constrained by what’s been done before, what’s been tried. We play it safe instead of making big moves towards transformation. And so I ask, what would you dream if you could? And how do we dream something new together?

I often remind people, particularly in the context of inclusion, that children, especially young children, are more adaptable, less bothered by the things that feel overwhelming to adults. When we open ourselves to trying new things – whether that’s working towards greater inclusion of children with different physical needs or learning profiles or shifting from English-dominant to bilingual worship – young people are more likely to see the benefits, the upsides, the possibilities. They’re less concerned with the question of “what if it doesn’t work?”

Things don’t work all the time. Kids know that. And so they also know that when they don’t work, you try something else.

This past weekend, the New York Times published an article about grandparents raising their grandchildren (gift link). Certainly this has always happened, but it’s become a particularly prominent social circumstance with the increase in opioid addiction in the United States. The author, Frances Dodds, is the sibling of a person in recovery and her parents are raising her sister’s four children.

Several things struck me about this article, but the first and especially specific thing was when the author noted, to describe just how common this situation has become, that there are three other families in the church school her nieces and nephew attend who finds themselves in the same circumstance. And it immediately raised the question for me, is that church doing something in particular that is reaching these families? Is it serving them in a way that helps to support them in the midst of what is a fundamentally traumatic experience?

I can’t answer that question, but certainly churches could. Maybe it’s a need your community has! Or maybe it is a story that is helping you refine your own lens on what might make your circle distinctive.

The author or this article is also a PK, so she’s got a certain fluency in the language of faith and she captured a valuable sentiment articulated by her father. Turning towards 1 Corinthians and all that “faith, hope, and love” talk, her father noted that “people don’t pay much attention to hope. Even though it’s there all the time, right behind love.”

But that’s not the whole of the sentiment. Frances, an expectant mother, observed that her parents had to stay alive to the contemporary moment in a way they wouldn’t necessarily if their children were all grown and flown, so to speak. Instead, because they have to continue to parent, she has observed in their experience “what a crushing, life-giving contagion hope can be.”

A crushing, life-giving contagion.

Yes, that is exactly what hope is. Overwhelming, spreading, and the soil that can birth something new. What will you hope into new life?

Let Us Pray

Loving God, source of Living Water, your streams carry us toward the hope of eternal life. We, who are your creation, are not miracle-workers, but the miracles themselves. Open our eyes so that we may truly see in our neighbors the miracles they are so that we may tend our hopes – heavy yet wonderful, contagious in their possibility transforming them together into good works, into hands that serve and doors that stand open. Amen.

Resource Round-Up

Many thanks to my pal the Rev. Silas for sending me this sweet Earth & Altar essay about singing and praying over one’s children in the challenging space of bedtime. It’s title, “Go My Children with My Blessing,” is, as the author notes, a Lutheran favorite, and I definitely grew up singing it regularly. This piece is just so tender.

Kate Bowler’s got some new resources for those of you in the thick of raising or coming alongside teenagers. You can find the free course here.

Amy Julia Becker has a great podcast about what a “good life” looks like through the lens of disability, faith, and culture. Catch her latest episode with Matthew Mooney that seeks to unravel the tragedy narrative of autism being put forth by RFK and others.

I know I’ve shared the song “Holy Now” before, but as I was writing above about how we are not the miracle-workers but the miracles themselves, it was back in my brain, so enjoy!

I chose Wake Up to Wonder by Karen Wright Marsh as my end-of-year gift to my Church School volunteers. First of all, it’s got a dream team of blurbs, but really I’m just trying to encourage folks (myself included - probably especially) to lean into the full scope of wonder and awe and inspiration in what already is or has been. And this book is full of beautiful models for that practice ranging from Hildegard von Bingen to to Howard Thurman. I hope you’ll find some time to dip into these little pockets of hope.

That’s it for now, friends. Off to dream up some new ways -

Peace,

Bird