Dear Friends,

The days hurry by – Holy Week is almost upon us.

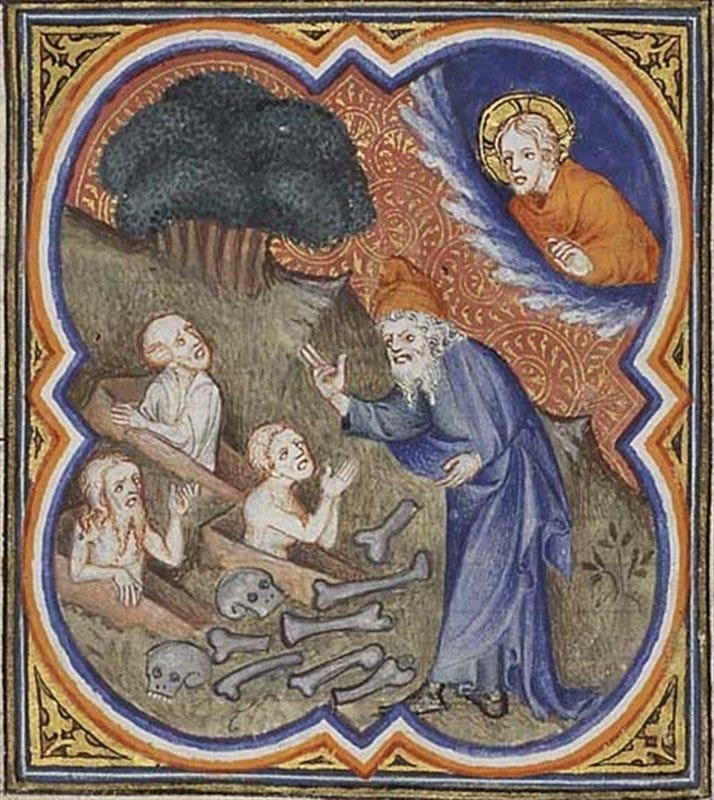

As we continue down this road, we find ourselves facing a curious slate of stories. This Sunday’s lectionary brings us two texts about unusual kinds of restoration: the Valley of the Dry Bones, from Ezekiel, which is often told during the Easter Vigil, and the Raising of Lazarus. In each, we see bodies that have crossed over death’s threshold made whole again. God’s power proves greater than death – but only for the moment.

There was something remarkable the first time I sat with Lazarus’s resurrection. It’s a conflicting story because of Jesus’s position in it. As I’ve heard some say, when Jesus raises Lazarus from the dead – after 4 days, no less, rather than 3 – it diminishes something about the resurrection that still lies ahead. But there’s a key difference: Lazarus still has to die again. We don’t see it or hear tell of that moment, but mortality – the natural existence of death – still holds fast to Lazarus’s body. Meanwhile, as the hymn goes, “We know that Christ is Raised and Dies No More.”

Following on this past Sunday’s healing of the blind man, ideas about restoration are in the air. Restoration to physical wholeness. Restoration of life after death. In Ezekiel, we even see the bones rejoined, as they shake off the dirt and become reanimated. And in the story of Lazarus, we even see the same idea as we do with the blind man: that Lazarus’s rising has happened so that others may witness the Glory of God.

A Troubled Thanksgiving

There are so many pieces of liturgy that are dear to me, but certain phrases have made a home deep inside of me, and one of those phrases is “for the means of grace and for the hope of glory” from the Order for General Thanksgiving in the BCP. Still, those words ring more clearly in their context:

Almighty God, Father of all mercies, we your unworthy servants give you humble thanks for all your goodness and loving-kindness to us and to all whom you have made. We bless you for our creation, preservation, and all the blessings of this life; but above all for your immeasurable love in the redemption of the world by our Lord Jesus Christ; for the means of grace, and for the hope of glory. And, we pray, give us such an awareness of your mercies, that with truly thankful hearts we may show forth your praise, not only with our lips, but in our lives, by giving up our selves to your service, and by walking before you in holiness and righteousness all our days; through Jesus Christ our Lord, to whom, with you and the Holy Spirit, be honor and glory throughout all ages. Amen.

Was I created, am I preserved in my ongoing days, for the means of grace and the hope of glory? Thinking particularly about what it means to have a disabled body in the context of last week’s healing passage, was I made this way so that the glory of God might be revealed? Or are those things separate? It’s a worrisome line and worthy of a great many words on the subject – but not right now.

Preaching The Word, Teaching Inclusion

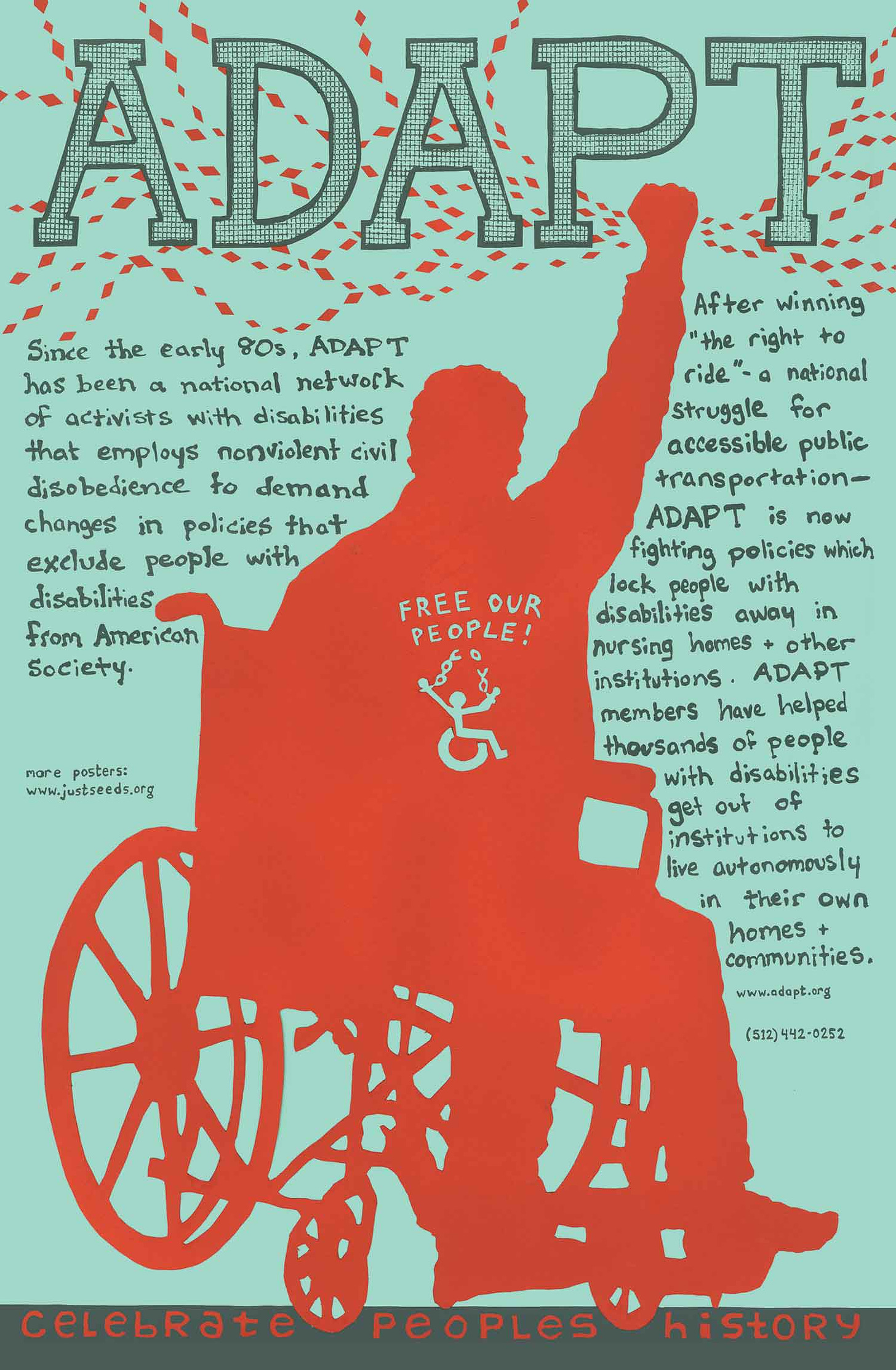

Last week, as priests and pastors and children’s ministers and people of all stripes working in churches attempted to make sense of the miraculous healing at the heart of the lectionary, some extremely important questions came up. But, for want of a world that feels comfortable talking about disability, things got messy. So let’s start with the essentials.

Disability is not only not a dirty word, it’s one of the only ways to avoid the damage that comes from using euphemisms to describe our own or other people’s lives. No one has referred to my sexuality as “an alternative lifestyle” since my grandmother when I was in high school. Inevitably, though, someone is going to utter the phrase “differently abled” or “special needs” when disability comes up, and I will feel their discomfort wash over me.

Amidst the anxiety around disability that was front and center last week came some questions of particular interest to the church school space. In particular, how do we tell stories like last week’s Gospel, how do we teach about disability, without doing harm? It’s hard enough to tackle these stories in a sermon with adults who have diverse life experiences that will inevitably include disability and who understand metaphor. Still, it doesn’t. have to be as complicated as people make it out to be.

I’m working on some resources for telling these stories and doing this work more generally (I’ll keep you posted), there are a number of simple places to start:

Look at your community. If you aren’t seeing disability representation (particularly among the younger 2/3rds because we will all become disabled if we live long enough), then there are probably some really good reasons why. Is your building physically accessible? How do you respond to questions about access (auditory access, ASL interpretation, access to the altar, low scent needs, the list goes on)? How do you support people who may not behave in ways you expect? Is your website accessible (hint: that’s more complicated to execute than you may think)?

Getting your congregation moving in the right direction on matters of access and inclusion can mean bringing in outside parties to talk to your community, provide trainings, and help you develop best practices. Amy Kenny, author of My Body Is Not A Prayer Request, offers a great checklist for starting to think through these topics.Start With Stories. One conversation I was blessed to have last week was about what to do in place of what are sometimes called “disability simulations.” Blindfolding people or asking someone to try to navigate a space using a wheelchair is not actually a realistic or helpful way of helping people develop an understanding of disabled people’s lived experience. But just like we use stories to understand other topics, like what people’s lives are like in other parts of the world, there are neutral and helpful stories that we can use to normalize disabilities. Some of my favorites that aren’t trying to be inspirational, but are open and informative, are Just Ask by Sonia Sotamayor and A Day With No Words by Tiffany Hammond, but it’s also important to learn where disability is hiding in the stories we already tell.

In Godly Play, for example, we have a story about Harriet Tubman. We can include Harriet Tubman’s brain injury in her story as simply something else about her – not as something that changes how we view her accomplishments, but as another piece of information. Where is disability in the stories we’re already telling and how can we make it visible?

There is always more to say, but as we continue to draw closer to Holy Week, we are all functioning at capacity, so let’s leave it here for now while remembering that we have work to do. And I’ll keep pondering whether my body is a means of grace – particularly for others, as the stories can make it seem. Or if this body, as it is, is a site of thanksgiving, not when it is restored in glory, but today, too.

Peace,

Bird